The Sum of Our Programming: Finding Humanity in Emotional Labor

Data paints. Plays music. Deals poker. Drinks at the bar. Tells jokes (or tries to). Dances. Keeps secrets. He cares for his friends. He creates a child. He experiences romance, and loss. He has a cat. Yet, during seven seasons of network television, Data’s exact nature remains a strangely open question. Characters repeatedly question his sentience. His personhood is perpetually portrayed as on uneven ground. Data himself is certain that he is not human.

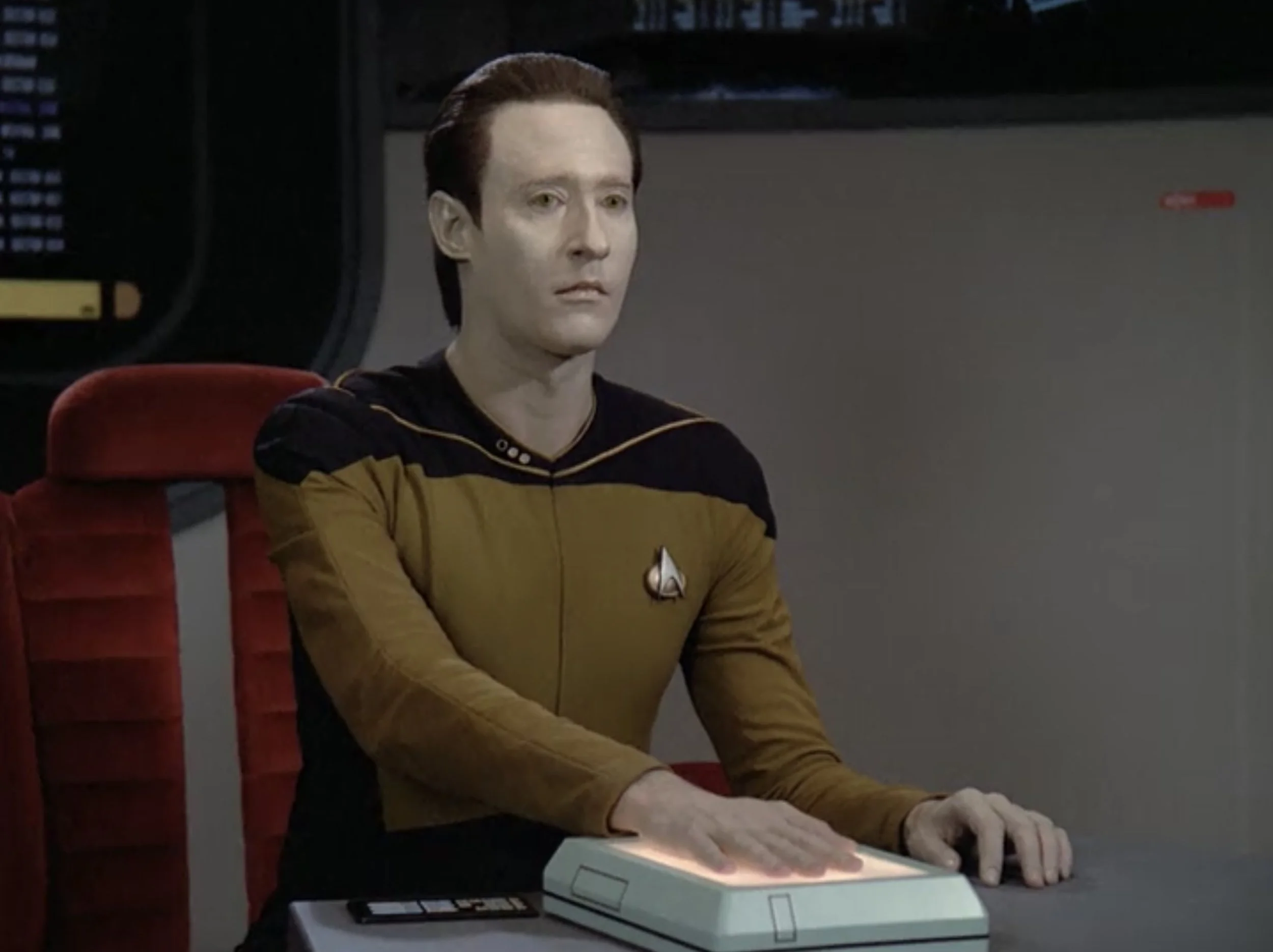

“The Measure of a Man,” 2x09, 30:15

From The Good Place to Frankenstein, artists have used characters with so-called artificial intelligences to explore the bounds of what makes a person a person. Is it self-awareness? Intelligence? A sense of self-preservation? The ability to feel? For Data, an android with a positronic brain, the true meaning of humanity is not internal, but relational. Humanity is to be found in the ways that people care for each other: how we anticipate each other’s needs, soothe our hurts, and care for each others’ bodies and hearts. What Data discovers is that humanity is found not in emotion, but in emotional labor.

Emotional labor has made for popular headlines lately, but it was first articulated decades ago by Arlie Russel Hochschild, the acclaimed sociologist and author of The Second Shift and The Managed Heart. Emotional labor is the work that a person does to manage the emotions of other people. It has proven to be an almost infinitely flexible concept, being used to describe the work of flight attendants and health care workers (as in Hochschild’s original examples) as well as parenting, house cleaning and maintenance, and navigating environments of sexual abuse. In all of these cases, individuals (and let’s be real, they are mostly women) take on work that is directly or indirectly in service of managing someone else’s happiness, anger, love, or contentment.

“The Offspring," 3x16, 12:00

One of the best things about Star Trek: The Next Generation is the way it makes emotional labor visible by literalizing it as work. While this is most bluntly true for Deanna Troi, the counselor who interprets others’ emotions for Captain Picard, this work is portrayed most thoroughly by Lieutenant Commander Data. Because Data’s deepest desire is to be human, he uses his capacity for observation and interpretation to develop a program that predicts human responses to specific actions. He is sophisticated in how he incorporates vocal tone, body language, facial expression, and other behavior cues into his interpretation of crew members’ intentions and meaning, and he is constantly refining his programming based on his experience. While the show often makes jokes at Data’s expense for interpreting people’s words too literally, his self-programming is so sophisticated that he has the ability to communicate nonverbally with other members of the crew.

As a woman watching this series, it was a revelation to me to see a man value communication so much that they would work hard to learn to do it well. It was a joy to see someone struggle to learn behavior that is so often treated, particularly for human women in the 21st century, as if it should be as natural as breathing. Watching Data struggle, without judgment, as he learns how to deliver bad news, buy a wedding present, use irony, or comfort a friend is comforting to me: Data knows, even if no other man will acknowledge it, that emotional labor isn’t just the key to being a good woman. It’s the key to being a good human.

“In Theory,” 4x25, 24:38)

During early seasons of The Next Generation, Data’s nature is treated as an internal question. Is he self-aware? Is he intelligent? Does he possess a consciousness? When he is literally put on trial to determine whether he is a person or the property of Starfleet, both prosecution and defense are largely concerned with whether or not Data himself has a soul or a self. Data himself, though, is always more occupied with his success in maintaining his relationships: with his friends, with romantic partners, and with his child, Lal. As Data helped raise Lal he asked for advice from Dr. Crusher, the only other parent he knew, about how to help Lal while she passed into sentience (a life stage that must be experienced, and not pre-programmed). Dr. Crusher advises Data to share his own struggles with Lal, so that she knows she isn’t alone when she needs love. It’s a poignant moment, because even as Data insists that he is “incapable of giving her love,” he is, in fact, showing his love by caring for her so devotedly. Later, when Lal succumbs to injuries to her positronic brain, she tells him that, since he cannot feel the love that he has for her, she “will feel it for the both of us.”

Humanity is about more than ego. It is more than self-awareness and self-determination. It is even about more than our own emotions. It is a key component of emotional labor that it often involves managing our own emotions, suppressing our own feelings of anger or betrayal in order to do the care work that needs to be done. Data understands this, too. He wants to experience human emotions more than almost anything else in his life, but when they endanger the crew and his mission he turns them off, at great personal cost.

To be human is to be a member of a community, a crew, that cares for each other and works hard to take care of each other. Data, like all human women, has struggled to prove himself a sentient being in the eyes of the law, but this is only a necessary, not sufficient, condition for humanity. Data continually searches for his humanity by enacting and improving his performance of emotional labor, just as we too look for safety, security, friendship, and love by caring for the emotions of our families, colleagues, neighbors, and friends.